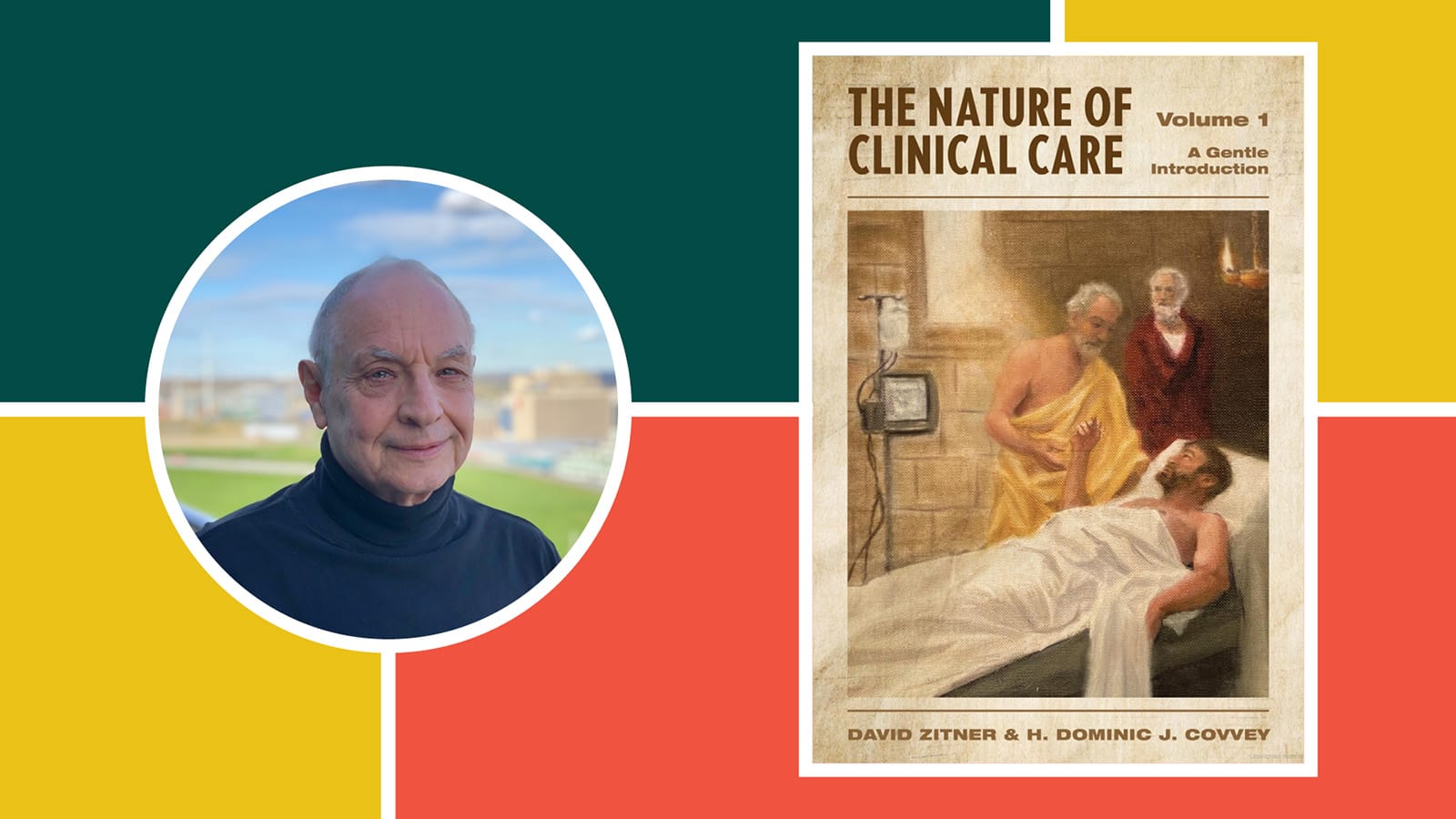

The following is a reflection composed by David Zitner, retired family physician in Halifax, in memory of the late Dominic Covvey.

David collaborated with Dominic, a health informatician and former professor at the University of Waterloo Professor on the series “Clinical Care: A Gentle Introduction” that relate the important ideas in clinical medicine so that patients, and non-clinicians working in health care collaborate, contribute to, and evaluate clinical care.

***

More than twenty years ago, Dominic Covvey and I met with clinicians, health informaticians, researchers and administrators to create “Pointing the Way: Competencies and Curricula in Health Informatics,” a guide for curriculum development in health informatics. Collaborators agreed that anyone working in health care must understand not only how health information is collected and used, but also important clinical ideas, including how to evaluate health, how diagnoses are made, how tests and treatments are judged, how to evaluate health systems and some basic ideas in mental health.

I used many of the ideas from “Pointing the Way” to encourage colleagues in the Dalhousie University, Faculties of Medicine, Management and Computer science to implement the first Canadian post graduate program in health informatics. An important component was the one semester course “Clinical Fundamentals for Non-Clinicians.” To everyone’s surprise, graduate students, with no previous clinical background and the one semester course were able to solve simple and complex medical problems including problems of diagnosis, testing, treatment, mental health and program evaluation. Graduates understood how clinical information could be used to measure the results of care and determine when changes to the health system are overall helpful or harmful.

After being out of touch for many years, Dominic was surprised to hear from me and was excited when he heard that people who know the fundamental ideas in clinical care could use computer support to solve important clinical problems and assess the value of solutions offered by clinicians or Dr. Google.

Both of us continued to be troubled by health care systems that reorganized but and did not systematically collect feedback to learn if the new systems were better or worse.

We developed a 7-year coast to coast collaboration, Dominic on Mayne Island, me in Halifax, Nova Scotia. We believed that by combining clinical expertise and experience with a non-clinical perspective we could develop easy to read and interesting text that would empower patients and help improve health services.

Dominic was a natural storyteller. I took a worthwhile program at the Narrative-Based Medicine Lab.

We started with different ideas about health, health care, the uses and abuses of health information and how to communicate. Over our 7-year collaboration we met virtually and wrote between discussions. Sometimes we raised our voices, but nothing about the project impaired our friendship. Our debates eventually produced a shared understanding of the most important health care ideas and how to describe them, as well as of trivia about the Oxford comma, and the use of singular “they.”

Narratives about engaged patients, who understand important ideas, showed that non-clinicians can improve their own care, contribute to finding solutions, and help doctors avoid mistakes.

Clinicians were convinced that Rose, a 78-year-old, woman, had Parkinson’s disease. Treatments were not effective and her gait continued to deteriorate. Eventually she realized her doctors had considered only the most likely, but not all, possibilities for her problem. She convinced the neurologist to do brain imaging that showed her symptoms resulted from normal pressure hydrocephalus. A neurosurgeon placed a shunt, her symptoms disappeared and she enjoyed eleven more years of high-quality life. Despite having little formal education Rose showed that an engaged patient can help in her own care.

A 30-year-old normally energetic woman, Jane, had blood tests and investigations for fatigue and sleep disturbance. Her doctor reviewed the blood work, told her she had a “depression”, caused by a biochemical imbalance and started her on anti-depressant medication. Subsequently, she asked her doctor which chemicals were imbalanced and was upset to learn that all her blood work had been normal. Feeling mislead and outraged by the white lie she decided to modify her diet, improve her exercise program, and gradually reduce her antidepressant medication. She felt relieved when she improved and realized her fatigue was a consequence of a busy lifestyle that interfered with self-care. Her participation helped her avoid the potential harms of excessive drug use, and the effect on self-esteem from a false belief that she had “biochemical imbalance”, a possibly chronic illness.

We produced a 3-volume series “Clinical Care: A Gentle Introduction” including a volume on general medicine, a volume on issues in mental health, and a third volume discussing health care systems.

So far, readers who have commented have suggest that the ideas and real-life anecdotes make the books useful and engaging. People understand that prompting doctors to consider all possible diagnoses helps avoid the harms from delayed understanding and treatment. They appreciate learning how to ask about the possible benefits and harms of treatment in ways that provide more than superficial answers. Some voice surprise to learn that problems labelled “mental illness” rarely have an associated biomarker, and appreciate learning that that when some problems, like thyroid or adrenal disease, are treated the mental health problems are also alleviated. Some readers expressed surprise when they realized that test results, seemingly objective, can be misleading, like fire alarms producing false alarms, or providing inappropriate reassurance.

As a clinician I’ve always had my home number in the phone book and my e-mail address is available. I’m looking forward to hearing more from former patients and the public about their experiences with health care. I am especially interested hearing about patient experiences where clinicians welcomed engagement or instances where clinicians found patient engagement aggravating.

More details about the first volume in the series is available from the publisher Friesen Press.